Unpacking My UAT Guide

For a number of years, I was responsible for converting a large number of, mostly manual, processes into an automated ticket logging system for a major UK company. Many of these processes passed through a number of teams on their road to completion, and they ranged from routine tasks like creating a new user account to the more complex process of getting new software approved for purchase and installation.

Often, the knowledge of how a process worked was stored only in the minds of the people that carried it out. To complete a project, I’d first start by getting everyone together that was involved to document the As Is. In many cases, this had never been done before.

Then, we would agree how that would look and work in the ticket logging system, what information we needed to gather from the user, who would need to do what, etc. etc. The project would get scheduled into an upcoming Sprint cycle, and then I would do the work.

All of that normally went smoothly and to plan. Even writing the code and developing the interfaces was pretty straight forward and would normally be completed on time. But then, time and time again, I would hit a road block, and the whole project would go off the rails.

User Acceptance Testing (UAT) turned out to be the point where things most often went wrong.

The problem was easy to spot (or so I thought): The people who requested the process automation project were too busy to test the new process automation project.

Which I saw as a Catch 22. I was trying to roll out a tool designed to save them time, but they didn’t have the time to test the new tool, and thus I couldn’t roll it out to save them time.

What I realised, and what changed everything, is that the problem wasn’t as obvious as I thought. It wasn’t a lack of time, but rather, a lack of understanding.

In the early days, I just assumed that as these individuals understood the process better than anyone and was involved in the design of the new process, when I handed them the new process, they would know what to do with it.

After all, if you know how to drive a car, and you buy a new car, you’ll know how to drive that one too. But that’s not what was happening here. It was more like they knew how to drive a car, and I had just handed them a brand-new aeroplane, expecting them to get in and fly away.

To solve this problem, I knew I would have to hold their hand through the UAT testing, and to do that I created a UAT Test Guide, that had the following information.

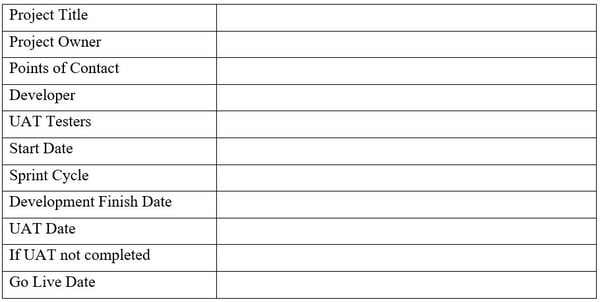

Page 1: Project Overview

The cover page to the document started with the project title then listed the key stakeholders, important dates and milestones, etc., and looked something like the following table.

- This project will be put on hold until UAT is finished, and then scheduled into the next available Sprint cycle to be rolled out.

- This project will be made live as-is, as subsequent projects are dependent upon it. Any changes or bug fixes will be scheduled into the next available Sprint cycle.

My goal on page 1 was to make it clear who was doing the UAT, when I needed it by, and what would happen if it wasn’t completed on time. And remember, all of this was agreed upon in the various meetings we had about the project, so I wasn’t asking them for anything they weren’t already expecting.

Page 2+: Testing Requirements

Page 2 is where I figured out that the people requesting this project, although intimate with the process, wouldn’t know where to start when it came to flying the plane I built for them. So, on this page, I listed a step-by-step process they could follow to test the new process. I wrote this in a similar vein to a user guide.

- Open a new ticket

- Enter the following information into the appropriate fields

- Name

- Request

- Etc.

- Etc.

- Click submit

- Etc.

- Etc.

These instructions typically took a ½ page to a page, and subsequent pages would have some key screen grabs and additional information on carrying out the UAT.

The idea here was to hand them the information to enter so they didn’t have to sit and wonder what to do next. Thus, saving them time and making it more likely they would do the testing.

At this point, all the backend and automatic testing had been completed, and I knew I had a functioning process. I wanted the testers to focus on the user interface and the forms that their team members would be accessing. This document was a lot about what to put in, and what they would get out of the new process, and, did that meet their needs?

Once they completed the first test, and understood the process, I encouraged them to run a few more with their own information, to see if they could break it.

Attachments

After the step-by-step instructions, I filled out the rest of the document with background information about the process. I included the process overflow diagram created after the early meetings, some of the key notes and tasks taken from the meetings, and a rather detailed description of what I changed in the software.

I did this so that when a tester came to me and said something wasn’t working the way they expected it to, we could go through the flow diagram and meeting notes to see if the information was originally captured correctly or was it misinterpreted. It often made understanding why something didn’t work as expected, quick and easy to figure out.

Remember: software testing is all about finding the root cause of a problem, and sometimes the root cause lies in the communication between individuals.

I would email this document to everyone involved in the project and explain in the email that it was now ready for UAT. I would highlight, again, the completion date for UAT and what would happen next, and what would happen if the UAT wasn’t completed.

At the ½ way mark through UAT, I would email the testers with a reminder, and again at the ¾ mark. I would include their Team Leaders in on the 2nd email. And these reminders were meant as a gentle nudge that the project is waiting for UAT completion.

I am happy to say, that once I implement the UAT Guide process, more and more projects went live on schedule. And the hour or two spent compiling the document was saved in time I would have spent trying to get people to do the UAT and the frustration of putting another project on hold.

.png)